FSU PC PARTNERS WITH CITY TO REDEDICATE HISTORIC BLACK CEMETERY

A journey that began with the search for two lost siblings’ graves led to a rededication ceremony last week at a historic Black cemetery in Panama City. Along the way, FSU Panama City students and staff participated in the cleanup effort, performing research and restoration.

“It was a cemetery of the forgotten, and we took initiative as an FSU Panama City community to come together and work on the project as a means to give back to the larger Panama City community,” said Associate Dean Irvin Clark, Ed.D.

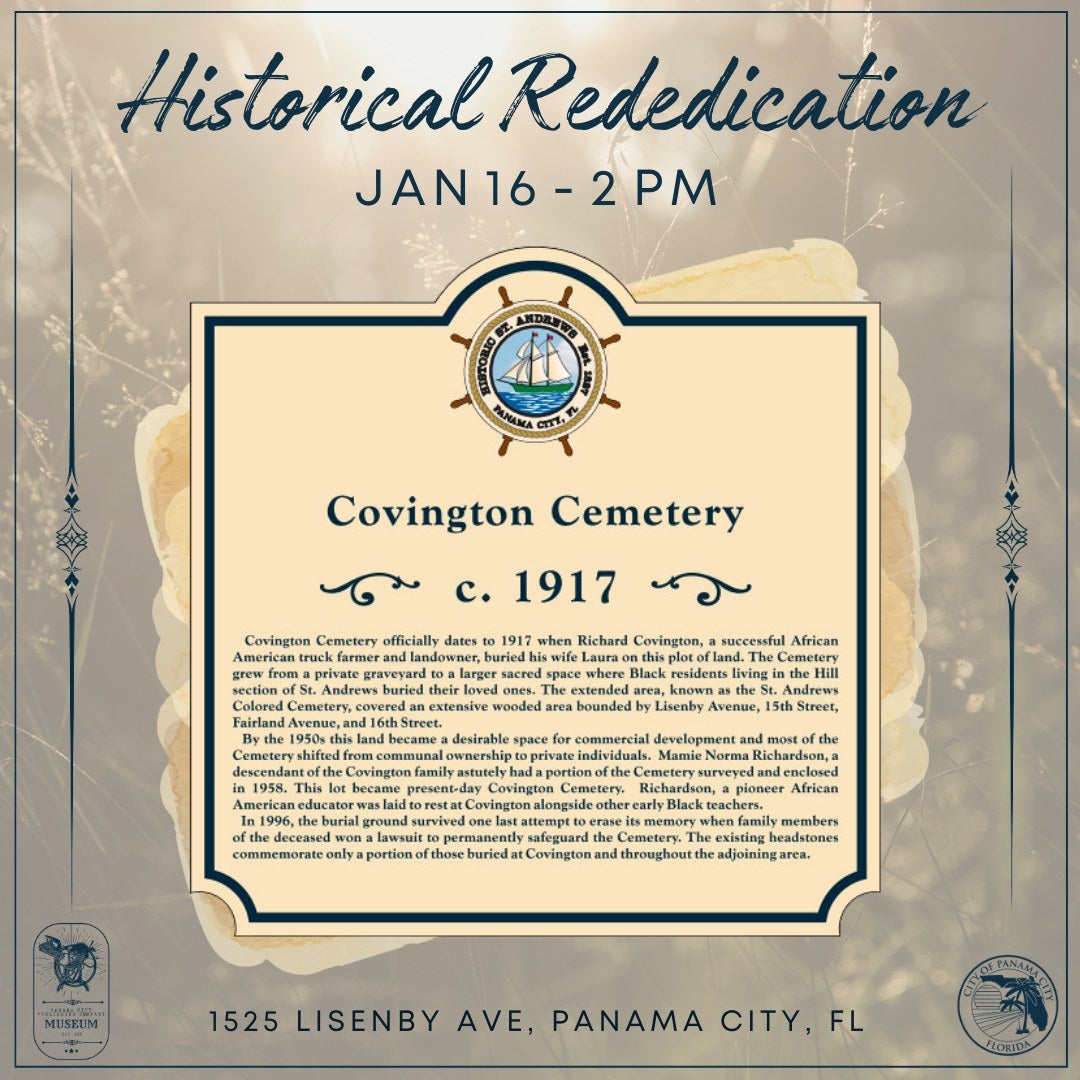

On Jan. 16, the City of Panama City hosted the dedication of a historic marker at the remnants of Covington Cemetery, which was a segregated cemetery for early Panama City’s African American residents.

“Significant figures in the African American community are buried there,” said Robert Cvornyek, Ph.D., assistant teaching professor in Social Science at FSU PC. “Mamie Richardson, who was a teacher at Glenwood, is buried there, by Lorain Hill, another teacher. That cemetery really does tell the story of almost every African American educator in early Panama City.”

FSU PC Professor Robert Cvornyek

The modern portion of the story began when Cvornyek received a call from Katherine Pierce and her sister Sandra, who were searching for the graves of their twin sisters, who had died shortly after their birth many decades ago. They knew their infant siblings were buried somewhere in the St. Andrews area of Panama City, but they didn’t know the exact location. Staff with the City of Panama City suggested that they search the cemeteries along Lisenby Avenue, which were historically Black burial sites.

When they did so, they were shocked by the condition of Covington Cemetery, a privately-owned plot at 1525 Lisenby Ave. Hurricane Michael had toppled trees in the cemetery, which became overgrown. Headstones were damaged. In addition, a camp of about 15 homeless people was discovered within the wooded area.

Cvornyek said the situation presented a moral dilemma of evicting people from a place where they had created a kind of sheltering space in order to clean up the final resting places of some of the city’s earliest residents. The homeless eventually were relocated with the city’s assistance, he said, and the cemetery was cleared of any environmental hazards, which opened it for reclamation and restoration.

HISTORIC PRESERVATION

“When I first heard about the need to cut up the downed trees and clean Hurricane Michael debris from a private cemetery, I became anxious to see the site,” Clark said. “When I saw it, my heart ached because the few head stones I could read made it clear to me that those buried there are part of Panama City’s collective history, and their gravestones tell stories of people who once lived, worked and loved, memorialized by a few carved sentences.”

Clark, who oversees Student & Strategic Initiatives, came on the first workday and wielded a chainsaw to help remove the fallen trees. Other staff also pitched in, joining Cvornyek’s students.

“At the time, I taught a course in historic preservation,” Cvornyek said. “The students worked on returning the headstones, which had some water damage and other things, to as near the original condition as possible. … The class also did genealogical work.”

The Pierce sisters have so far been unable to locate the resting places of their siblings, possibly because a large area of the cemetery’s former footprint is now occupied by businesses and parking lots.

Janice Lucas, Panama City commissioner for Ward 2, said the cemetery that remains is “probably less than half” of the original footprint. She added, “We have reason to believe there are bodies buried outside of the perimeter of this cemetery.”

Janice Lucas, Panama City commissioner for Ward 2

But the effort initiated by the sisters’ search brought a new lease on life to the historic location, as what was originally a preservation and restoration project became a research project, delving into the local history and families of the area.

“‘Love’ is not too strong a word here,” Cvornyek said. “It really was a labor of love—restoring the dignity of a sacred place goes beyond politics. The students felt a sort of deeper connection to the people buried there and the community they represented.”

The work inspired Cvornyek as well. He praised the “university students engaging outside the classroom in a loving and thoughtful way that is significant to their community.”

Clark now hopes an FSU PC registered student organization will “adopt” the cemetery and help maintain its landscaping, while FSU PC continues to use the historic site for future research opportunities.

CEMETERY DEDICATION

Panama City Commissioner Josh Street arranged for the city to take over the care and maintenance of the cemetery as part of the agreement to transfer the property from the private owner to the city. The city installed a new fence and cut the grass, Cvornyek said, and a marker was created by the Historic St. Andrews Waterfront Partnership, which has installed similar signage throughout the community.

“I was born and raised in Panama City, not far from where we are standing, actually here in the St. Andrews community in the historic African American community called The Hill,” said Lucas, an FSU PC Notable ’Nole (’89), who unveiled the marker at the dedication ceremony.

Historic marker

Cvornyek wrote the inscription, which reads in part:

“Covington Cemetery originally dates to 1917, when Richard Covington, a successful African American truck farmer and landowner, buried his wife Laura on this plot of land. The cemetery grew from a private graveyard to a larger sacred space where Black residents living in the Hill section of St. Andrews buried their loved ones. The extended area, known as the St. Andrews Colored Cemetery, covered an extensive wooded area bounded by Lisenby Avenue, 15th Street, Fairland Avenue and 16th Street.“By the 1950’s, this land became a desirable space for commercial development, and most of the cemetery shifted from communal ownership to private individuals. Mamie Norma Richardson, a descendant of the Covington family, astutely had a portion of the cemetery surveyed and enclosed in 1958. This lot became present-day Covington Cemetery. Richardson, a pioneer African American educator, was laid to rest at Covington alongside other early Black teachers.

“In 1996, the burial ground survived one last attempt to erase its memory when family members of the deceased won a lawsuit to permanently safeguard the cemetery. The existing headstone commemorate only a portion of those buried at Covington and throughout the adjoining area.”

Many people in the local community are not aware of the historic significance of places in Panama City, Lucas said.

“They think the things that they see about the early segregated times happened somewhere else. But you know, when I was born in 1961, this was a segregated community,” Lucas said. “So, it’s important that we continue to acknowledge and then work to correct those injustices that have happened. But also, it's a part of humanity; we judge society about how we treat our young, how we treat our elderly and how we remember those who have gone on before us.”

Lucas said the dedication and the marker meant a forgotten chapter of local history was finally acknowledged.

“It means that we are finding a way to address the hurts and wrongs of the past,” she explained. “So often, that doesn’t happen because people get triggered, emotions run high—and that doesn’t stop the fact that there is a wrong that needs to be righted. That is what’s important to me, that we keep moving forward to correct those injustices.”

Lucas said she hoped the community would learn from the message of the marker and the search for the Pierce sisters’ graves.

“There are people who are unseen, who feel unimportant, marginalized, expendable,” Lucas said. “And when we take time to acknowledge the sacred burial ground of African Americans, we are saying that our ancestors are important, and we revere the lives that they lived and are doing what we must do to acknowledge that and thus bring life and hope that into those that live who believe that no one cares about them.”

(Editor’s note: FSU PC students Katie Dier, Destiny Hansley, and Justin Sowell contributed to this report.)